....for if there is one type of man to whom I do feel myself

inferior , it is the coal miner.'

George Orwell, The Road to

Wigan Pier, 1937.

Coal from the Yorkshire coalfields was one of the major source of power behind the global industrial revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries, and the first half of the 20th centuries. It was the middle east of its day. In 1950 the North Notts/South Yorks coalfields alone employed 40,000 miners and was the most productive in the UK. In 1980 four deep coal mines on this website's area alone employed around 4,000 people.

Trades Union banner, Kiveton Colliery 1910. Opencast mining, Fence nr Aston 2010

By 1993 most of the local pits had been shut, and 3,000 jobs and 400 years of coal mining has come to an end (or maybe longer see the reminiscence's of Jon Laynes for archaeological evidence of bellpit mines in Aston cum Aughton unearthed in the 1940s). Maltby colliery remains open and produces about 1 million tonnes of coal with 500 miners.

Coal is close to the surface around here, some stream beds are made of coal in the undulating countryside, and in the 20th century strip mining has extracted millions of tons of near surface coal. For example, a strike call banner from 1948 claimed that near to norwood there was a coal seam of '200 acres of good quality coal, 4ft. 6ins. thick'. There were 4 deep mining pits in the villages area that closed in the early to mid 1990s i.e. Dinnington, Kiveton, Shireoaks and Thurcroft, (and dozens of others of the Yorks and Notts coalfields), but its use goes back much further than that:

In 1285 the burning of coal was discouraged in London because of its sulphurous smell, and in 1685, 50 people died in 1 week from coal smog (London was England's only really large city, most 'cities of the period had populations smaller than present day Aston cum Aughton, e.g. Norwich in 1500 had a 12,000 population and was the 2nd largest city in England).

In 1873 when the industrial revolution was in full swing 700

people died in a London coal smog. The toll rose remorselessly and

in 1880 there was a London smog that killed 2,000 people in 1 week

and 90 days per year were recorded as having a yellow/brown/orange,

well, sulphurous coal smog. The smoggy scenes so beloved of

contemporary 19th century writers like Arthur Conan Doyle (Sherlock

Holmes) and Robert Louis Stevenson (Dr Jeckyl and Mr Hyde) plus

countless Jack the Ripper films, were dependent upon coal smog!

London was the most populous and energy consuming city in the world

back then, but it was coal that supplied the UK's energy needs, and

the Yorkshire coalfields supplied much of the black gold. So, back

in time to...

In 1873 when the industrial revolution was in full swing 700

people died in a London coal smog. The toll rose remorselessly and

in 1880 there was a London smog that killed 2,000 people in 1 week

and 90 days per year were recorded as having a yellow/brown/orange,

well, sulphurous coal smog. The smoggy scenes so beloved of

contemporary 19th century writers like Arthur Conan Doyle (Sherlock

Holmes) and Robert Louis Stevenson (Dr Jeckyl and Mr Hyde) plus

countless Jack the Ripper films, were dependent upon coal smog!

London was the most populous and energy consuming city in the world

back then, but it was coal that supplied the UK's energy needs, and

the Yorkshire coalfields supplied much of the black gold. So, back

in time to...

In 1598 local (to this website) coal output was over 2,000 plus tons a year. Kiveton pit opened in 1866 and was one of the oldest in the UK. Dinnington pit opened in 1904 and Thurcroft pit in 1913, but pits have opened, closed, and merged since 1700. Take a look at the plaques commemorating the local collieries on this site.

In 1900 1,100,000 miners were employed in the UK (this site doffs its predominantly Yorkshire cap in respect to the miners of Wales and Scotland, the midlands, Northumbria, etc.). Wherever they where, the death rate was high in the 1930s and '40s. That was a death rate attributable to obvious causes such as mining disaster of course, there were very many more lingering deaths due to lung diseases and other disabilities from fired, prematurely retired, and disabled coal miners. Durham Mining Museum has compiled an excellent resource if you want to know more at http://www.dmm.org.uk/stats/index.htm.

In 1966 swinging Britain produced 188 million tons of coal from 480 mines. In 1992, after the Govt. minister Michael Hesseltine slashed an 800 year old industry, energy contracts for power generation went to North Sea gas generators (called at the time the 'dash for gas'). In 1992 there were 58,000 miners producing 88 million tons. By 1996, when the industrial slaughter was finally over, bar the shouting and there were 18,000 miners producing 40 million tons, and all the pits on the website area were closed. 3,000 local miners had lost their jobs (plus related employees). Remarkably little provision was made by John Majors Conservative government for the badly affected mining communities. I know from experience they were less fragmented communities before the pits were closed.

Locally, Thurcroft pit closed in 1991 with the loss of around 1,000 jobs. Dinnington closed in 1992 with 1,000 jobs lost, and Kiveton pit closed in 1994 (1,000 jobs). As you may have gathered, deep pits employed about 1,000 people!

Closed colliery sign, Kiveton 1999

There's still plenty of near surface coal around though, and applications are still being made to open cast (i.e. strip mine) large tracts of territory. Rother Valley Leisure park was built on (or in?) a 1970s open cast mine, and it had been open casted earlier that century also. The offers often come with incentives attached such as the offer to make the old pit yard area into a marina for the Chesterfield Canal, or even to make it navigable between Kiveton and Killamarsh. However, open casting can involved increased pollution, very heavy freight traffic, and 20+ years of letting the gouged earth heal (see below) and there are battles fought throughout the coalfield areas against and for opencasting. This is my personal view - those who have worked the opencast and deep mines have (with passion) legitimately expressed opposite views (hello Frank!) and point out that opencasting can free £ millions for post-mining reclamation. However, the 1990 ish Treeton opencast on the site of the old Orgreave coking plant (scene of violent struggles during the 1985 miners strike) is not a good advertisement for opencasting.

"A slag heap is at best a hideous thing, because it is so planless and functionless. It is something just dumped on the earth, like the emptying of a giant's dustbin. On the outskirts of mining towns there are frightful landscapes where the horizon is ringed completely round by jagged grey mountains, and underfoot is mud and ashes and overhead the steel cables where tubs of dirt travel slowly across miles of country. Often the slag heaps are on fire, and at night you can see the rivulets of fire winding this way and that. Even when the slag-heap sinks, as it does ultimately, only an evil brown grass grows on it, and it retains a hummocky surface." George Orwell, the Road to Wigan Pier, 1937.

There was a 'burning tip' in Kiveton and many other places as late as 1970. I can remember as a kid peering into a crevice maybe 20 cm wide and 100 cm deep at the dull red glow, and smelling the sulphurous fumes. It must have been very dangerous but was just part of the scenery to us kids.

The environment around all the old mining villages would be greatly improved if the old slag heaps were properly reclaimed as parkland (see reclamation pics below).

Above: Kiveton colliery 1983 and a similar shot 1999, taken from the pit tip looking north-east. The elevation is lower as the spoil heap has been landscaped a few hundred feet lower into a gentle rolling hill.

Above: Kiveton station 1983 and a similar shot in 1999

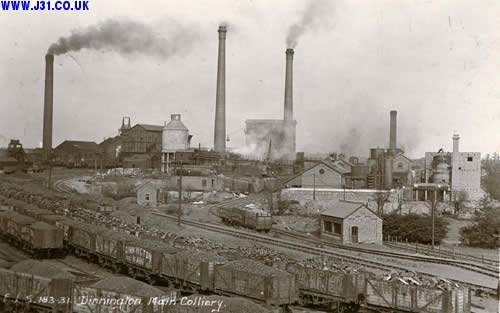

Below: Dinnington Colliery in its heyday (courtesey Alan Burke of MosboroughWeb)

Above: Methane vents above old mine shaft 2007

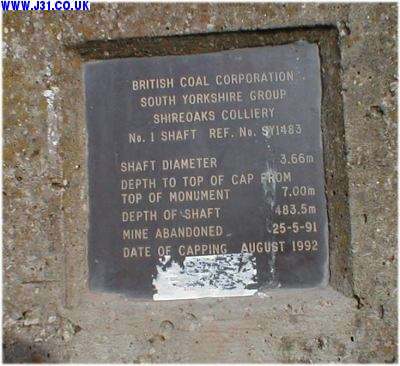

Above:Capped mine shaft marker, Shireoaks pit

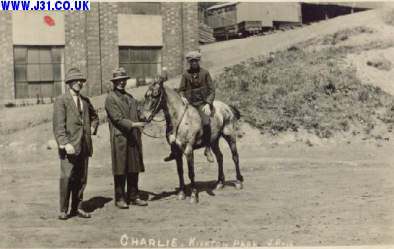

Below; a pit pony called Charlie, Kiveton Colliery 1920

The old mine workings have not gone away, but are slowly filling with methane and water, and from time to time, seismologists detect micro earthquakes from gallery collapses. The old mines have these vents to release the methane in a controlled manner, and it may be harnessed as a power source. According the the Sunday Times (27 Jan 2008) these old pits are leaking 60,000 tonnes of methane per year.

I know that the old Shireoaks shaft has had a methane collector (by Alkane) above it tat burns methane in situ and generates electricity from it that's fed directly to the grid.

As mentioned above, the pits closed in the early 1990s but the scene was set for their closure after the miners lost the 1984 strike. The miners in this area were on strike for most of a year. In addition to their loss of salary, state benefits were also denied them and their allowance of 1 ton of coal a quarter was also cut off. This resulted in striking miners sifting through the slag heaps in the winter snows of Jan-March 1985 for the nuggets of coal buried in the mud and shale, much as Orwell had described unemployed miners doing 50 years earlier in The Road to Wigan Pier. It was a struggle in which Margaret Thatcher's government effectively broke the power of the trades union movement for the remainder of her terms in office. This area was at the centre of that conflict. The local working mens clubs were hotbeds of striking miners of the National Union of Mineworkers (NUM) planning action such as the raising of teams of flying pickets.